There will be a screening of "Pyeongtaek: Korean Farmers' Struggle for Land" on Monday, March 19th. The farmers are at risk of being permanently excluded from their land to make way for a US Military base by the end of March.

It's urgent that we take action against in support of Korean sovereignty!

Where: Liberty Hall, 311 N Ivy

Portland, Or 97227

When: 7pm

40 minutes

For information, to help with food or cash donations, or to host a screening of your own, contact Miae Kim at newmediacreation@yahoo.com

Friday, March 16, 2007

Asian Reporter Reviews Documentary

http://asianreporter.com/film/2007/11-07pyeongtaek.htm

EVICTION. Elderly Pyeongtaek farmers are overwhelmed by an evicting police force in filmmaker Miae Kim’s Pyeongtaek: Korean Farmers’ Struggle for Land. (Photos/Jin Jae Yoen)

From The Asian Reporter, V17, #11 (March 13, 2007), page 11.

A little rice village and a super power

Counting wins and losses

Pyeongtaek: Korean Farmers’ Struggle for Land

A documentary film

Produced and directed by Miae Kim, 2007

By Ronault L.S. Catalani

The U.S. administration assures us, and reassures our world, that we are winning. Winning. That threats everywhere are managed, that the Axis of Evil is isolated, that the ominous, sleeping dragon (China), just now rousing, will be contained by overwhelming American military might. Planted firm, garrisoned everywhere.

Late last summer, award-winning South Korean and West Coast producer, now Portland filmmaker, Miae Kim packed up her hastily acquired recording gear and went to tiny Pyeongtaek village. She went to sit and eat with even tinier rice-farming grandelders, before their eviction from their barely significant but wondrously green little plots.

It’s hard to imagine how these two images, indeed how these two realities, intersect. Super power and rice farmer. But it’s easy to guess who will win when they do.

Speculating on possibilities is actually not necessary. By the end of March, we will have winners and losers. Elderly farmers’ lands will be cleared for U.S. military expansion. That’s why Oregonians’ seeing this film is so important. Take family, make witness. It is essential to our times.

"We will lose our roots. I am heartbroken," says Grandpa Soeng Kyoeng Soen, slouched in a folding chair in front of crushed homes, his barb-wired rice paddy just behind. "My father and my mother built all this when they were alive. I am heartbroken."

If that doesn’t say it all, Ms. Kim’s documentary includes observations from social and economic human-rights activist Christine Ahn, a fellow of the Oakland Institute, and commentary by Medea Benjamin, founding director of Global Exchange and co-director (with "peace mom" Cindy Sheehan) of Code Pink. Probably three of the most profound voices for sanity in our anxious times.

"It was very agonizing to be an American," says Ms. Benjamin, answering this article’s opening quandary, and connecting those dots only apparently so disparate. "To be going into a village being destroyed because of my government’s policies." Big dots. Ugly ones. They are mythic in proportion, as tragic as Korean history.

When and where push comes to shove

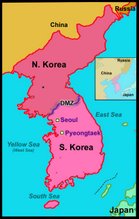

Korea is that vulnerable North Asian peninsula long locked between aggressive giants. Imperial China and Japan and Russia, to name a few. The United States Army based there for 60 years. Every last one of those mighty empires has assured eras of peace and prosperity. For all.

According to Ms. Kim’s film, some Pyeongtaek village families have been forcibly removed from their homes three times by successive armies. Human-rights activist Christine Ahn notes that these elderly farmers, who just like her parents grew up during Japan’s brutal colonization, survived Korea’s awful war against communism, then persisted through the new South Korean Republic’s ferocious dictatorship, "now have to live through this, during the final stages of their lives. And how could we allow such a thing to happen?"

How could we?

What are our intimately human costs for grand-scale economic globalization, and U.S. military domination?

Who wins and who loses? Watch carefully close-ups of 70-year-old ladies clutching riot-geared cops’ crowd-control shields, shields held just as desperately by boys who could be their grandsons. Who is shielding what?

Listen quietly to an unnamed priest, showing up out of nowhere, making a solemn Mass out of nothing, between splintered timbers and pulverized brick. What is he softly saying after his service to those startled and ashamed soldierboys behind their hardware, as he asks for their hands?

This is terrific documentary filming. This is top-drawer peace making.

Who will win, who is prevailing, in this terribly human intersection is not as clear as we had worried. Or wished.

It’s not over until it’s over. And although Portland is far from Pyeongtaek, we are far from over.

Go see this film; go with people you love.

* * *

Nota: To help with food or cash donations, to host your own Pyeongtaek screening, or for more information, visit director Miae Kim’s website at.

Please also see Code Pink’s Pyeongtaek website at.

The Pan-South Korea Solution Committee’s website is.

* * *

EVICTION. Elderly Pyeongtaek farmers are overwhelmed by an evicting police force in filmmaker Miae Kim’s Pyeongtaek: Korean Farmers’ Struggle for Land. (Photos/Jin Jae Yoen)

From The Asian Reporter, V17, #11 (March 13, 2007), page 11.

A little rice village and a super power

Counting wins and losses

Pyeongtaek: Korean Farmers’ Struggle for Land

A documentary film

Produced and directed by Miae Kim, 2007

By Ronault L.S. Catalani

The U.S. administration assures us, and reassures our world, that we are winning. Winning. That threats everywhere are managed, that the Axis of Evil is isolated, that the ominous, sleeping dragon (China), just now rousing, will be contained by overwhelming American military might. Planted firm, garrisoned everywhere.

Late last summer, award-winning South Korean and West Coast producer, now Portland filmmaker, Miae Kim packed up her hastily acquired recording gear and went to tiny Pyeongtaek village. She went to sit and eat with even tinier rice-farming grandelders, before their eviction from their barely significant but wondrously green little plots.

It’s hard to imagine how these two images, indeed how these two realities, intersect. Super power and rice farmer. But it’s easy to guess who will win when they do.

Speculating on possibilities is actually not necessary. By the end of March, we will have winners and losers. Elderly farmers’ lands will be cleared for U.S. military expansion. That’s why Oregonians’ seeing this film is so important. Take family, make witness. It is essential to our times.

"We will lose our roots. I am heartbroken," says Grandpa Soeng Kyoeng Soen, slouched in a folding chair in front of crushed homes, his barb-wired rice paddy just behind. "My father and my mother built all this when they were alive. I am heartbroken."

If that doesn’t say it all, Ms. Kim’s documentary includes observations from social and economic human-rights activist Christine Ahn, a fellow of the Oakland Institute, and commentary by Medea Benjamin, founding director of Global Exchange and co-director (with "peace mom" Cindy Sheehan) of Code Pink. Probably three of the most profound voices for sanity in our anxious times.

"It was very agonizing to be an American," says Ms. Benjamin, answering this article’s opening quandary, and connecting those dots only apparently so disparate. "To be going into a village being destroyed because of my government’s policies." Big dots. Ugly ones. They are mythic in proportion, as tragic as Korean history.

When and where push comes to shove

Korea is that vulnerable North Asian peninsula long locked between aggressive giants. Imperial China and Japan and Russia, to name a few. The United States Army based there for 60 years. Every last one of those mighty empires has assured eras of peace and prosperity. For all.

According to Ms. Kim’s film, some Pyeongtaek village families have been forcibly removed from their homes three times by successive armies. Human-rights activist Christine Ahn notes that these elderly farmers, who just like her parents grew up during Japan’s brutal colonization, survived Korea’s awful war against communism, then persisted through the new South Korean Republic’s ferocious dictatorship, "now have to live through this, during the final stages of their lives. And how could we allow such a thing to happen?"

How could we?

What are our intimately human costs for grand-scale economic globalization, and U.S. military domination?

Who wins and who loses? Watch carefully close-ups of 70-year-old ladies clutching riot-geared cops’ crowd-control shields, shields held just as desperately by boys who could be their grandsons. Who is shielding what?

Listen quietly to an unnamed priest, showing up out of nowhere, making a solemn Mass out of nothing, between splintered timbers and pulverized brick. What is he softly saying after his service to those startled and ashamed soldierboys behind their hardware, as he asks for their hands?

This is terrific documentary filming. This is top-drawer peace making.

Who will win, who is prevailing, in this terribly human intersection is not as clear as we had worried. Or wished.

It’s not over until it’s over. And although Portland is far from Pyeongtaek, we are far from over.

Go see this film; go with people you love.

* * *

Nota: To help with food or cash donations, to host your own Pyeongtaek screening, or for more information, visit director Miae Kim’s website at

Please also see Code Pink’s Pyeongtaek website at

The Pan-South Korea Solution Committee’s website is

* * *

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)